Murtagh (Part 2)

STATS

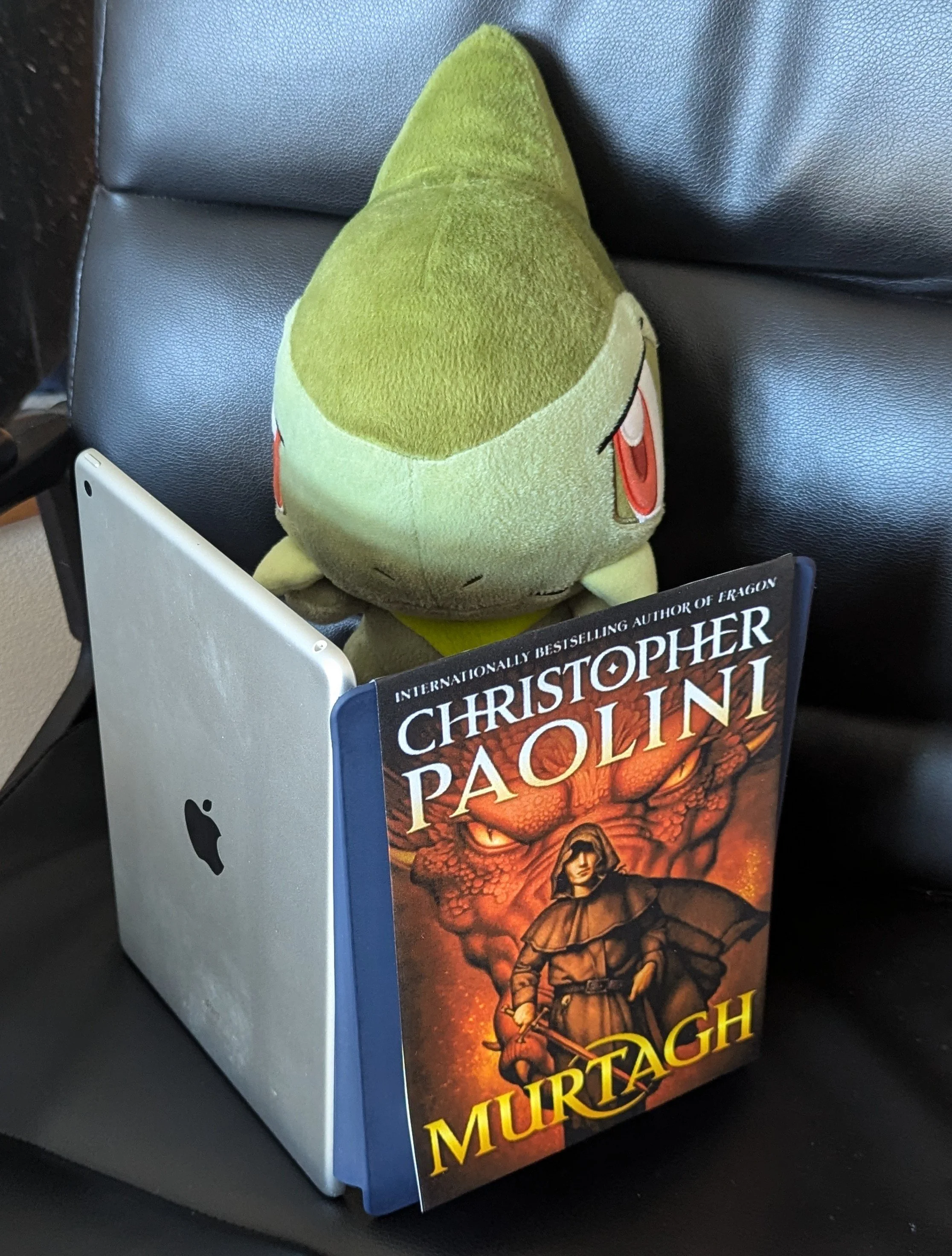

Title: Murtagh

Series: N/A

Author(s): Christopher Paolini

Genre: Young Adult Fantasy (Epic)

First Printing: November 2023

Publisher: Alfred A. Knopf

SPOILERS

Mild spoilers for Murtagh will be included throughout this review, through I will keep the first paragraph of each section as spoiler-free as possible. Heavy spoilers will be confined to clearly labelled sections.

Heavy spoilers for the Inheritance Cycle will be included throughout the review. These shall not be marked.

WORLDBUILDING

The worldbuilding of Murtagh is its most positive aspect. Paolini is still deeply passionate about this world and understands how its disparate pieces fit into a cohesive whole. He focuses upon extrapolating and expanding upon the existing elements rather than introducing wholly new was, and when he does introduce new elements, they are molded to fit what already exists.

Unfortunately, while Paolini is still passionate about his world, it was not his first priority. At multiple points, he breaks his own rules for the sake of driving his chosen plot forward. I could chalk any one of these issues up to an editing mistake, but this many form a definite pattern.

The following is not going to be a comprehensive breakdown for all of Alagaësia. Rather, I want to focus on elements that have been added by or elaborated upon by Murtagh.

The Name of Names

Those of you who read the Inheritance Cycle will recall the Galbatorix’s ultimate weapon, which Murtagh later used to help Eragon defeat him, was the name of the Ancient Language. This is effectively a master override code for magic. During its brief appearance within the Inheritance Cycle, we saw it applied towards the following ends:

Assigning names in the Ancient Language to previously unnamed entities.

Changing or erasing oaths sworn in the Ancient Language.

Dismantling spells cast using the Ancient Language.

Enchanting Galbatorix’s throne room so that the only people inside who could use magic based on the Ancient Language would have to invoke the Name of Names first. (The story frames it as only Galbatorix being able to use magic, but Murtagh uses the Name of Names to switch the effect off, which he shouldn't have been able to do if his access to magic was completely blocked.)

The Name of Names (which, for brevity’s sake, I will just call, “the Name” from here on out) comes with two weaknesses. To my recollection, Paolini didn’t explicitly spell either of them out, but they were at least heavily implied by how the Name was applied.

The Name has no effect on magic cast without the Ancient Language. Eragon and the dragons use wordless magic to cast the final spell that defeats Galbatorix.

Because the Name hands incredible power to anyone who knows it, the wielder has to take precautions to avoid sharing the Name whenever it is used. Galbatorix did this by adding an addendum to any spell where he used to name, automatically erasing the memory of him speaking the Name from anyone within earshot.

The Inheritance Cycle ends with Galbatorix’s death, leaving knowledge of the Name in the hands of six characters: Murtagh, Arya, Eragon, and their dragons.

I’m sure some of you have already spotted a problem here: the Name is an instant-win button. The reason the Eragon didn't automatically win every fight with magic was that it was common practice for magicians to place wards on both themselves and soldiers under their protection, negating those spells that would take less effort than simply killing the enemy with physical weapons. With the Name, those wards are irrelevant. Murtagh is coming into this story with the ability to automatically negate any ward that keeps him from ending fights instantly with magic.

So, how does Paolini juggle this issue?

The Good

Early in the story, we learn that Bachel is incredibly skilled in wielding wordless magic. She is able to enchant protective charms to provide Dreamers with wards against magic. This is a defense that Murtagh can't break with the Name. What’s more, this is tied specifically to Bachel. There’s not a whole cabal of spellcasters who can ignore the Name.

Murtagh is also immensely hesitant to use the Name as the story progresses because the knowledge can be stolen from him. It’s all well and good for him to use it on random thugs, but there’s always a risk that a spellcaster will overhear it, even with him using the memory-erasing addendum, or else tear it from his mind. He therefore reserves it for situations where he is absolutely certain that no one will end up overhearing and learning the Name. Once he is aware of Bachel’s protective charms, those situations almost completely dry up.

Going back to the discussion of Zar’roc in Themes - I will remain spoiler-free here - the Name is employed for that.

The long and short of it is that, on a conceptual level, Paolini manages to carry the Name forward without damaging the world.

The Bad

We are introduced to Bachel’s protective charms in the third chapter, a mere 7% of the way through the story. She is mass-producing them on such a scale than every thug under the command of some trader has one. One pops up later in the possession of a magician. There’s nothing to indicate that the random guards allied with the magician don’t have them, too - Murtagh assumes that they do. In other words, Paolini may not have made a cabal of spellcasters who can ignore the name, but he made every single enemy, from the minions to the master, immune to this game-changing element.

This could have been fine if the discovery of this protective charm, the game-changing element that negates the game-changing element, were the inciting incident. It’s not. Murtagh was already on a collision course with Bachel because the aforementioned trader has an evil rock, one that he was warned about at the end of the Inheritance Cycle. The protective charm is, at most, a plot coupon that he shows to people to aid his investigation.

The bit about having knowledge stolen from Murtagh makes sense, but Paolini applies it inconsistently. In that first encounter, when Paolini wants to show off what Bachel’s charms do, Murtagh is all too happy to whip out the Name, despite being surrounded by a half-dozen enemies and a bar filled with random civilians. However, later in the book, when he is in an underground tunnel where the only person who could possibly hear him is a random guard who is unlikely to have any magical training and who is about to be incapacitated anyway, he starts panicking about being overheard.

It all feels incredibly forced. Paolini is taking something that was previously presented as incredibly rare and dangerous and making it a default setting. Simultaneously, he’s taking a reasonable precaution and amplifying it into a paranoid excuse.

The Takeway.

It seems highly unlikely that Paolini thought through the impact that the Name would have on future stories in Alagaësia when he wrote Inheritance. He is now bending over backwards to remove it from the story so as to preserve conflicts. I respect the effort - at least he’s working within the established rules of the world, rather than saying, “Thorn got a bit bigger, so now Murtagh can’t access the story-breaking power anymore, because that’s simply how it works now” - but it is still badly done.

If the Name is such an obstacle to telling stories, then the solution would have been to tell a story dedicated solely to eliminating that obstacle. I was chatting about this with the folks on the Bastion Discord server (formerly known as the -iverse Discord). Just spit-balling ideas, we came up with multiple iterations of the following two story concepts:

Have the Name leak out somehow, thereby putting that immense power in the hands of either one very dangerous magician or spreading chaos as multiple magicians learn and abuse it. Murtagh then needs to go on a quest to alter the nature of magic / the Ancient Language, thereby invalidating the Name and taking this power off the board.

Have the nature of magic / the Ancient Language be altered by some unknown force, thereby making the invalidation of the Name into the book’s inciting incident. Murtagh could then go on a quest to learn why and how this happened.

Otherwise, Paolini should have just leaned into it. He should have let Murtaugh have this godlike power that allows him to insta-win most conflicts. Bachel’s wordless magic should have been saved for limited situations that would give it a sense of importance.

The Rules of the Magic System

In the Inheritance Cycle, magic has the following rules:

It is controlled by thinking in the Ancient Language while tapping into a magical energy source. Verbalizing a spell is considered safer, since it eliminates the risk that a stray thought can corrupt a spell’s wording, but it is not necessary. Wordless magic is possible, but likewise very dangerous and unpredictable outside of a few specific cases (like the magic used by dragons to fly and breathe fire).

Spells cast using the Ancient Language are extremely literal. The magic user has some room for interpretation based upon word choice - the example given by Oromis in Eldest is that, when using the word, “Fire,” the magic user’s intent dictates how the fire is conjured and what form the fire takes - but the spell cannot go against what is spelled out. Eragon curses Elva instead of shielding her because he incorrectly conjugated a verb; Oromis acknowledges that Eragon’s true intentions may have softened the curse, but the fundamental nature of the curse was set in stone. Additionally, wards can only defend against things that are explicitly identified as threats and often need to have holes left in them so that the warded person can function. Lastly, if a spell is not given conditional clauses to terminate it at the user’s will, it cannot be stopped until it either achieves its goal or drains all of the energy that fuels it (thereby killing the user).

Completing a task with magic requires the same energy as completing the task by purely physical means. This energy will typically come from the life force of the magic user, but it can be drawn from another living being whose mind is touched by the magic user (such as a Rider’s dragon) or from a reservoir stored within a gemstone. The energy demand of a spell also increases with distance from the target. If a spell’s energy is cut off (either by the magic user dying, the gem that fuels it being drained, or a failsafe in the spell to prevent the spell from killing the user), the spell ends.

Magic can be disabled via either a drug that blocks a person from tapping into magical energy sources (which was introduced all the way back in Eragon) or by using the Name (as established in Inheritance).

Objects can be enchanted to apply the effects of spells even if the user of said object cannot perform magic for whatever reason, provided that the object is provided with a power source (usually a gem integrated into it). A good example of this was Oromis’s sword, which was laced with spells to protect him if he should have a seizure during a battle.

So, how does Paolini do in terms of following his own rules?

The Good

For the most part, Paolini is consistent with what he wrote in the Inheritance Cycle.

Murtagh needs to deal with minor inconveniences (like getting bitten by a goat) as a result of having loopholes in his wards that he was either unaware of or hadn’t deemed to be worth the trouble to ward against. He kills a monstrous fish that was warded against harm by weaponry by stabbing it through the head with a human bone. He bypasses wards on stationary objects by thinking through what those wards are meant to protect against and then either exploiting their weaknesses or their power source. (I have my issue with how he puzzles through these problems, as covered back in Voice and will cover more later, but the logic he uses is sound within the context of the world.)

The long and short of it is, Paolini respects his magic system and the intelligence of his readers. Things make sense.

The Bad

At least, they make sense until they get on the way of some thing Paolini really wants to do.

There are two glaring instances of Paolini throwing out the rules even as he pretends to be respecting them. One of these we will get to in Plot - it’s a contributor to why the story implodes around the 80% mark. The other is a moment where Paolini breaks Murtagh’s character to not only default to Eragon’s voice but also pat himself on the back for his own cleverness.

When Murtagh visits the Dreamers, Bachel encourages him to stay the night. She knows he’s not going to simply stay in his room, so she posts a pair of guards. Murtagh realizes that Bachel will have warded them against any form of harm (which, given that she is using wordless magic, she has a lot more leeway with). He will need to bypass the wards before he can incapacitate them and sneak out to do his investigation.

His solution is the harm them while lying to himself that he is not harming them.

He decided to risk it. As with all magic, intent mattered, so he concentrated on the fact that both men appeared tired. It was late, and they ought to be in bed. It was be best if they slept, for their own good.

With that firmly in mind, Murtagh cast the same spell he’s used on the guard in the catacombs under Gil’lead: “Slytha.” Sleep.

He released the energy for the spell in a carefully controlled trickle over the course of a half minute or more.

This violates three of the rules.

The most obvious and devastating issue is that this flies in the face of what happened to Elva. Eragon’s intentions did not fundamentally change the nature of the curse. If wards would designate a sleep spell as harmful, then no amount of thinking really hard would change that.

Murtagh cannot control the trickle of magic if the entire spell is just the one word. This would have killed him if it didn’t work. We got at least one very clear example in the Inheritance Cycle of Eragon nearly killing himself with a one-word spell.

Not spelled out here is that Murtagh leaves the sleep spell running as he sneaks off to do his investigation. We are explictly told that he ends the spell after he comes back. However, no mention is made in the interim of the increasing strain this must be having on his magic, despite the fact that several minutes (if not an hour) pass and the fact that it sounds like he walks a hundred meters or more away from them.

In case it’s not clear why these points break the world, allow me to provide a hypothetical. Let’s say that there was a religiously motivated serial killer who believes that death is followed by an eternal life of bliss with the gods. This serial killer would be deeply convicted that, by killing people, he is doing the most beneficial thing he possibly can for them, sending them out of this world of suffering. Would Paolini seriously argue that said serial killer could bypass all wards and casually annihilate whole cities worth of people with one of this setting’s Words of Death (the low-energy killing spells) because he sincerely believes that he is doing it all “for their own good”?

Now, for Paolini patting himself on the back. Right after Murtagh knocks out the guards, we get this.

When no one came to investigate, Murtagh allowed himself a pleased chuckle. As much as he hated to admit it, the way Eragon had used magic on Galbatorix had been a stroke of inspiration. No one seemed to thinkof guarding themselves against the good, only the bad.

It wouldn’t last, of course. Over the years, word would spread from magician to magician, and eventually no capable spellcaster would leave themselves open to well-meaning attacks. A contradiction, that! But a reality all the same. Regardless, Murtagh wasn’t about to lament Bachel’s ignorance. As long as the technique continued to work, he’d use it and be grateful for it too.

Of course, he still didn’t know for sure if the guards had wards, but he would have been shocked if they didn’t.

Translation: “Yes, I know I am breaking my setting. Please just accept that this won't ever be a viable solution after this book. Just enjoy how clever I was back in 2011.”

This is also one of those reasons why this book feels like it was written by AI. Eragon didn't defeat Galbatorix by lying to himself that something harmful was actually beneficial. He consciously chose to do something that was simply not harmful, gifting Galbatorix with understanding of the consequences of the Galbatorix’s own actions. Furthermore, this was an act of wordless magic, thereby bypassing the prohibition on using the Ancient Language for magic within the throne room. Did Paolini forget what he himself wrote?

What makes this self-congratulatory moment all the more strange is that Murtagh actually does something that properly reflects what Eragon did later in the book: he suffocates warded guards by solidifying the air in front of their faces. Did Paolini not realize that scene would have been a better place to make the connection, not to mention that it doesn't break his setting?

(Also, this is one of those moments where Murtagh’s voice sounds off. He does not read like this in most of the rest of the book.)

The Catastrophic

Ever since Eragon, magic has been either wordless or controlled via the Ancient Language. This is a very strict binary. We learn as the series progresses that this binary was implemented by the Grey Folk to make magic safe for humanoids to use. They specifically bound magic to their language (which became known as the Ancient Language). No other magic words exist. Thus, though we see spellcasters among humans, elves, dwarves, Urgals, and Shades, we do not see a single individual violate this binary.

…

Apparently, the Urgal language can control magic now.

At the same instant, he mouthed the Urgal word that Uvek had taught him: “Shûkva.” Heal. It felt strange to work magic without the ancient language, but the word served its purpose nonetheless, and the charm triggered.

Why does this work? How does this work? Was this charm prepared using the Ancient Language and then keyed to activate when a specific word of Urgalish is spoken? We were specifically told by Oromis that spells are cast by thinking in the Ancient Language, not by that speech itself (since, otherwise, spells could spontaneously manifest from random noises). This works because the Ancient Language is bound directly to magic. So why would making a noise in a different language trigger the spell?

If this is indeed possible, why isn’t everyone doing this? Why didn't Galbstorix or the dwarves or the Varden mass-produce an item (such as, say, a wand) that allows any footsoldier to unleash a magic spell simply by holding the item and shouting a word in their native tongues, rather than grinding through the effort of training magicians to use the Ancient Language? We know the mass production capacity exists, as Nasuada financed the Varden by having magicians make lace, plus Galbatorix fielded hundreds of soldiers enchanted to feel no pain. Actually, given that last example, a physical item wouldn’t be needed. Just enchant soldiers directly so they they can hurl fireballs when they shout, “Glory to the Empire!”

What possessed Paolini to break his setting like this? Did he just not want Urgal shamans to use the Ancient Language? It’s not like them knowing the Ancient Language would be a huge stretch. They have existed in Alagaësia for millennia, fighting humans and elves all the while. If they learned human tongues (which would have evolved considerably) in that time, learning and retaining the language that never changes because it is rooted to the magic system should be relatively easy.

The Dreamers

I’ve harped on negatives this far, but these issues mainly come down to Paolini making mistakes regarding continuity with what came before. When it comes to new material - namely, the Dreamers and all elements connected to them - it slides into Alagaësia with very little issue. The results are not flawless. However, I feel these are issues with the Characters or Plot, not the worldbuilding in and of itself.

The Faction

The Dreamers, also know as the Draumar, are a decentralized cult built around the worship of Azlagûr the Dreamer. They build their communities around places where vapors released by Azlagûr leak to the surface, such as the valley of Nal Gorgoth (featured in Murtagh) and, formerly, the Hall of the Soothsayer (under Galbatorix’s castle, which he used as his favored torture chamber in Inheritance). These vapors give the Dreamers shared dreams (hence their name) of an acolyptic event in which Azlagûr will wipe the world clean and establish a new order around the Dreamers. The visions and their connection to Azlagûr have given the Dreamers a deep reverence of dragons and a penchant for Lovecraftian art and architecture. Their cabal has spread its fingers throughout Alagaësia and it preparing to mobilize against Nasuada’s restored Empire.

There is not much more detail that I can provide about the Dreamers themselves. They are a creepy cult with sinister intentions for the world. There is nothing deeper to them than that. Any time Paolini elaboratrs upon them, it is to reinforce how alien and disturbing they are.

That being said, as mentioned in Commentary, this is functional for the story being told. We don’t need to understand the Dreamers to understand that their efforts to bring Azlagûr’s visions to fruition are a bad thing for the characters and world we are invested in. It’s sort of like how The Empyrean is not hurt by venin being generically evil demonic beings. They exist to give an existential threat a face. Sometimes that is all a story needs.

Also, since I often comment about a lack of necessary religious worldbuilding within a book, I’d like to highlight the Dreamers as an example of where more religious worldbuilding would actually be a bad thing. The more we understand about the Dreamers, the less alien they become, and thus the harder it is for them to function in the particular way Paolini needs them to for the story to work properly. Restraint pays off here. I suspect that this minimalistic approach may not hold up if the Dreamers continue to play a role in future stories and thus become less of an unknown, yet for now, this limited availability of information is ideal.

Bachel

Bachel is the current Speaker of the Dreamers, serving as cult leader, intermediary for Azlagûr, and interpreter for the cultists’ visions. I’ll get into her more when we talk about characters, but for now, I want to touch upon what she brings to the worldbuilding.

First, Bachel is a half-elf, the daughter of an elf woman who joined the Dreamers and a man native to Nal Gorgoth. It’s not clear whether she has an elf’s immortality, but she does have a physique beyond that of a human.

Second, in addition to being incredibly skilled with wordless magic, Bachel has reservoirs of magic that goes far beyond what elvish ancestry can explain. At one point, she demonstrates her power to Murtagh by shaking the entire valley of Nal Gorgoth. Paolini never actually explains how she does this. It could be that she draws magical power from Azlagûr, or it could be that she is connected to Azlagûr and got him to shake the valley.

Third, Bachel consumes vast amounts of food and drink in a given sitting, without it ever affecting her physique or health. I don’t recall Paolini ever establishing that elves consume abnormally more food than humans or dwarves, so I assumed this had something to do with her connection to Azlagûr. However, this is another thing Paolini does not explain.

Overall, Bachel, and the nature of the Speaker as a whole, is an enigma. Thst works for this story. These unanswered questions don’t break anything, at least, not by the end of the book.

The Vapors

The vapors released by Azlagûr are known by the Dreamers as the Breath of Azlagûr. They induce visions of the future. It is not clear if these are possible futures, a set future, or merely something Azlagûr is thinking very hard about. However, it does seem like they take a while to get results. Bachel tries to stall Murtagh so that he will spend as long as possible breathing the vapors on and shaving visions.

In concentrated does, the vapors can also function as a mind control gas, robbing the affected target of independent will. Humans and dragons are affected by this equally; he Speaker and others sworn to serve Azlagûr seem to be immune to this effect. It’s unclear whether the Speaker is the only person who can influence someone affected by the vapors or if anyone can give that person orders, but for the purposes of Murtagh, the distinction is not important.

Allies

Not long after Murtagh reaches Nal Gorgoth, he learns that at least one of the Forsworn visited the valley. It is later revealed that Nal Gorgoth is both the place Galbatorix visited after the death of his first dragon and where he and Morzan fled to after stealing Shruikan. Durza also spent time here. This particular bit of lore has rammifications for the plot. In isolation, it merely helps to anchor the Dreamers as a part of the established setting.

In the present, the Dreamers have allies throughout the nobility and merchants of Alagaësia. Among their allies are disenfranchised nobles who suffered severe losses with the overthrow of Galbatorix and see the Dreamers as a path to reclaiming wealth and power. Again, this works in isolation and helps to give the Dreamers a foothold.

Azlagûr

Azlagûr the Dreamer - also known as the Devourer and the Firstborn - is a dragon so ancient, so massive, that the act of him waking up and emerging onto the surface of the planet would devastate Alagaësia.

The Dreamers revere dragons as aspects of Azlagûr, but Azlagûr himself seems to hate modern dragons for some unspecified reason. Bachel indicates that she helped Galbatorix because she foresaw that he would wipe out the dragons out, which seems to imply that Azlagûr wants them all dead. Given that the images of dragons in the Dreamers’ village look different form modern dragons, my best guess is that modern dragons descend from a bloodline of dragons that once warred with Azlagûr’s bloodline, but this is purely headcanon. (Believe me, we will be coming back to this point.)

I strongly feel that Azlagûr was a stroke of brilliance on Paolini’s part. It seems like Paolini’s goal with the Dreamers was to introduce some light Lovecraftian elements to his setting. Rather than throw generic Great Old Ones into the pot, he took an existing element of his setting - the dragons - and expanded upon it to fulfill the role he needed. Most of what Azlagûr brings to the table is an expansion upon elements that existed in the Inheritance Cycle:

His immense scale is an extrapolation of how dragons never stop growing as they age.

The fact he has slumbered so long thst he has been forgotten by the world fits with a mention in Inheritance about ancient dragons spending most of their time sleeping.

Azlagûr’s ability to share visions with others ties into the mental powers all dragons possess.

If he is the reason why Bachel was so magically powerful, that is a reflection of the Rider bond.

His ability to provide Bachel and other Speakers with visions of the future ties into Angela accurately foretelling the future using dragon knucklebones.

Rather an overcomplicating his setting by adding something wholly new, Paolini went back to what he’d already established.

State of the Empire

Murtagh is set “approximately one year after the events of Inheritance” (to quote the Inheritance Cycle wiki). Alagaësia is still recovering from Galbatorix’s reign and the war to overthrow him as well as adapting to Nasuada’s regime.

I think Paolini did a good job with this. Outside of the obvious matter of whose flag is being waved, the changes to the world are pronounced enough to be noticed but not so radical as to feel extreme. There are elves and dwarves in the human settlements of the Empire, but in numbers that make sense for new diplomatic or economic ties; it doesn’t feel like the Empire is suddenly hyper-cosmopolitan. Newly minted currency with Nasuada’s image is just beginning to be circulated. Those who lost loved ones in the war are still deep in the mourning process.

One element that is a particularly nice touch is how Paolini handles the public’s feelings about the regime change. Outside of the nobility - both those who lost wealth and power when Galbatorix fell and those who gained it - there’s a palpable sense that everyone just wants to mourn their loved ones and move ons. There’s a scene where Murtagh pretends to be a veteran from the war to deceive an officer, and the officer asks him what battles he fought in while pointedly avoiding asking who he fought for. Galbatorix’s conscription policy and forced loyalty through the Ancient Language, elements that were emphasized in the Inheritance Cycle, play a big part in this. Those who fought for the Varden understand that the Empire’s soldiers weren’t given any choice in the matter, and those who fought for the Empire just want to put their lives back together. No one seems interested in holding grudges (again, outside of the nobility).

CHARACTERS

This was not a strength of Paolini’s writing in the Inheritance Cycle. For Murtagh, it aspect where many of the issues previously covered (and some we haven’t) properly manifest. Murtagh and Thorn are interesting characters, but Paolini waffles the execution of their ideas. As for the new characters introduced, they serve functional roles within the story, but there’s nothing deeper to them.

Murtagh

Murtagh’s characterization in this book is much what one might expect after reading the Inheritance Cycle. He is brusque, cynical, and direct. The trauma inflicted upon him and Thorn by Galbatorix (which we previously covers in Themes) weights heavily upon him. This all leaches into his narrative voice, making him feel distinct from Eragon.

An element that is introduced to within this book is Murtagh’s charisma and his skill at deception. At multiple points, we see the ease with which Murtagh fabricates a false identity and adopts a persona perfectly suited to manipulate whomever he’s interacting with, whether that person is a town watchman or a court page. He always knows the right amount of detail to deliver to deflect suspicion and the right amount of theatrics to engage in to win people over. This makes sense when one considers his background. Murtagh may not have studied the works of the greatest elven scholars under the tutelage of an ancient Dragon Rider, but he did receive the best education that was available in the Empire and spent may formative years dealing with the intrigues of Galbatorix’s court.

It’s good that Murtagh has these skills, as he can’t solve problems the way that Eragon can. The first fight scene in the book clearly demonstrates that Murtagh lacks the enhanced physique that we are used to for Eragon; we are also reminded early on that his magical prowess from the Inheritance Cycle was a function of him having an Eldunarí at his disposal from Eldest onward. Paolini also takes care to establish that Murtagh knows very little of the Ancient Language. Galbatrox limited his training to prevent Murtagh from learning enough to be a threat.

This is great. It’s engaging. Murtagh offers us both a fresh perspective on Alagaësia and a different type of hero to follow. His limits open up so many opportunities to surprise us with fresh solutions. His past opens up opportunities to explore themes that weren’t engaged with when Eragon was the protagonist.

Which is why it is so frustrating that Paolini squanders or tosses out all of these things.

As covered back in Themes, Paolini tries to tackle all aspects of Murtagh’s trauma at once. It’s disjointed. Rather than feeling like the trauma is part of Murtagh’s identity and that he is healing from it over time, it feels like the trauma was something Paolini begrudgingly acknowledged. This aspect of the book reads as though Paolini just wanted to get over Murtagh’s healing process so that it wouldn’t impede his creativity in future books, so he tacked on a bunch of small moments and called it a day.

As for Murtagh’s limits, they are all handwaved.

Murtagh has limited vocabulary in the Ancient Language? It’s fine. He already knows all the vocabulary that he requires to solve problems in this story, plus he’s facing an enemy who doesn’t even use the Ancient Language, plus he just happens upon and picks up a dictionary for the Ancient Language that he can use to look up more words.

Murtagh has less magical strength than Eragon? It’s fine. Either Thorn or a gemstone are always on hand to support him when power would be a stumbling block.

Murtagh needs to solve problems with guile instead of raw intellect? Just kidding. He’ll puzzle through ever problem the way Eragon would.

Murtagh has less physical strength than Eragon? It’s fine. The only times that actually matters, he has the support of another character with the necessary physical prowess.

Then comes the matter of voice. When it comes to solving problems or just analyzing the world around him, Murtagh stops sounded like the world-weary cynic and becomes a more analytical and arrogant version of Eragon. These traits made sense for Eragon - I daresay they were part of Eragon’s charm - but it always feels like a jarring character shift for Murtagh.

I’ve said before (and will reiterate here) that it feels like Paolini isn’t comfortable writing Murtagh. It’s one thing to talk about giving Murtagh his own story so that he can grow and explore the world. Actually writing a story to take advantage of everything Murtagh offers and accommodates his limits was another matter entirely.

Thorn

Thanks to this book, Thorn is now the most fleshed-out of all dragon characters in this setting.

While Paolini does write his dragons as characters (excepting situations where there is a narrative purpose at play), they are very shallow, to the point of barely having any more meat on them than Violet’s accessories in The Empyrean. They exist to facilitate the stories of their Riders.

Saphira is exactly what you’d expect of the magical companion of a blank-slate slef-insert protagonist. Her only discernable character traits, that being her pride and her desire to protect Eragon, speak more to the worldview of dragons as a whole than anything unique about her.

Glaedr was basically Saphira, but with wisdom and experience, exactly what one would expect from a dragon who accessories a wise Mentor archetype like Oromis.

Thorn was a silent, animalistic brute within the Inheritance Cycle because Murtagh was a slave of Galbatorix for most of that story.

In Murtagh, Thorn gets more depth. His trauma actually is explored properly. We get a sense of the psychological scars he’s suffered, with him feeling immense self-loathing for how his scars control him. It’s not especially deep, but there’s enough here that you can see him as an individual, rather than merely Murtagh’s accessory.

That said, there is a glaring problem with Thorn’s agency. He doesn’t have any.

Saphira and Glaedr may not have been deep characters, but there was still a sense that they were doing what Eragon or Oromis asked of them of their own free will. They either agreed with their Rider’s chosen course of action, were going along with that action because it aligned with their personal motivations, or were backed into a corner (such as when Nasuada extorted Eragon and Saphira into separating during the events of Brisingr). The only dragons who felt like they were acting at the whims of their riders were, again, Thorn and Shruikan.

In this book, though, Thorn does whatever Murtagh tells him to. Paolini has him put up a token protest to Murtagh going into danger alone or to Murtagh insisting that they stay among the Dreamers to investigate things, but you can tell from the moment he opens his mouth (or, to be more precise, this mind) that he’ll go along with what Murtagh wants in the end. The one exception to this is a scene where Thorn and Murtagh seemingly reverse positions on the issue of staying to investigate the Dreamers, with Murtagh suddenly insisting that they flee while Thorn insists that they stay. In that circumstance, Murtagh comes around so quickly that it doesn’t read as if Thorn persuaded him. It instead reads like Murtagh was doubting himself and Thorn reminded him of his own rationale (i.e. that Thorn had no little agency in that situation that he could only parrot Murtagh’s own position to keep Murtagh on the rails of the plot).

Thorn does push back against Murtagh when his claustrophobia is triggered. He won’t go into caves or tight groves of trees no matter how hard Murtagh pressures him, and Murtagh needs to consult him before taking Thorn into a village to ensure that Thorn is comfortable with the space between the buildings. However, I think this was only done to service the exploration of Thorn’s trauma. If Paolini was not chasing a theme here, I highly doubt that Thorn would have shown even this little bit of backbone.

Overall, Thorn reads like a better-written version of Andarna. He may have better characterization than her (in that he has characterization), yet his presence was a stumbling block to the story Paolini wanted to write. Murtagh needed to be on his own for most of the story in order to access locations Thorn couldn’t enter (like cities or caves) or confront people without a dragon at his back. Paolini therefore wrote Thorn as a doormat who’d agree to whatever course of action Murtagh proposed, including sitting around waiting for extended chunks of the story while Murtagh did things alone.

Bachel

Bachel is a cult leader who is sincere in her beliefs.

That is as deep as her characterization runs. There are other things we can say about her - namely, her magical abilities and her nature as a half-elf - but those are worldbuilding notes. They are what she is, not who she is.

Narratively, I don’t think this is a problem in and of itself. This book required that the Dreamers be represented by a powerful figure whom Murtagh couldn’t understand or reason with. Bachel may be an archetype rather than a character, but for the role she plays, that's more than enough.

Bachel’s shallow characterization does play into the pattern of Paolini not empathizing with the perspectives of religious persons. She reads like a very negative stereotype of a religious leader. I get the feeling that Paolini just copied what he saw in other works, rather than actually thinking through her behavior and psychology. That said, I don’t feel that Bachel is the reason that Paolini’s biases hurt the story. The only decision she makes that feels at-odds with her characterization was clearly the result of the hand of the author forcing the plot, rather than the author not understanding how she might approach problems.

Uvek

My feelings towards this character are the same as Admad from A Master of Djinn - I like him, but he is narratively irrelevant, surfacing only to fulfill tasks that he really wasn’t needed for.

Around 70% of the way through the book, Murtagh is imprisoned hy the Dreamers. Uvek is the only other inmate. Uvek spends the next 15% of the book giving Murtagh pep talks this go nowhere and contributing to the disastrous collapse of the plot. He then provides Murtagh with extra muscle in the early parts of the climax.

There’s this big deal made over Uvek and Murtagh becoming blood brothers. I’m sure that will be relevant in future books. As it stands, Uvek is a massive waste of time. So much contrivance and nonsense goes into the implosion of the plot that removing Uvek from the picture wouldn't change anything. Paolini could have mangled the exploration of Murtagh’s Galbatorix-induced trauma just as well without him.

Lyreth

This is another character who could have been cut outright, though unlike Uvek, he did have a strong narrative reason to exist, at least in concept.

Lyreth is the scion of one of the noble families that lost power when Galbatorix was overthrown. When Murtagh was a boy in Galbatorix’s court, Lyreth was one of the boys who bullied him. Time is taken to call out that Lyreth was the most weaselly of the bullies, turning on his brethren when it benefitted him to do so. Murtagh bumps into him about halfway through the book, at which point Lyreth tries to recruit Murtagh as a figurehead for a movement to overthrown Nasuada. He later resurfaces as a miniboss from Murtagh to bulldoze through.

In concept, Lyreth makes sense as a part of this story. He represents an aspect of Murtagh's trauma to be overcome. He also acts as the face for an antagonistic faction that will probably have a presence in Book V and beyond.

The problem is that he’s redundant in both roles. Murtagh's childhood trauma is explored through flashbacks (and, as touched upon in Themes, this trauma ended up feeling like it was included out of obligation rather than because Paolini wanted to build a story around it). The Dreamers also fulfill the role of a destabilizing presence to threaten Nasuada’s hold on power. All that Lyreth offers outside of that is his role as a miniboss, but because he lacks any real important to the narrative, this aspect ends up feeling like a revenge fantasy rather than something necessary for the story.

Alín

This is the character that genuinely angers me. Through her, Paolini’s failure to understand religious people destroys his plot. A full analysis of that self-destruction has to wait until we cover Plot in two weeks, but for now, we can cover how her characterization telegraphs the disaster to come.

Much like Bachel, Alín is a shallow stereotype: the one good person in the insane cult, the virtuous soul who is clearly being exploited for her naivity. She displays open reverence for Murtagh and especially Thorn. Though she is a true believer in Azlagûr and is loyal to Bachel, she yearns to learn more of the world before the coming apocalypse wipes it away.

After just a couple scenes with Alín, it becomes blatantly obvious that she will betray the Dreamers and help Murtagh in some fashion. This poor, naïve, ignorant little girl just needs the enlightened, rational man to tip his hat and show her how her entire religion is a lie, and she will throw her entire life away for him. All we’re waiting for is the scenario for our hero to share his wisdom.

There is nothing objectively wrong with this trope from a literary perspective. It just needs to be executed properly. The development of said girl needs to follow a logical chain of cause and effect. Because Paolini does not seem to be capable of writing religious characters, he skips the chain of cause and effect and just jumps to the conversion because That’s Good, despite everything he’s established pointing towards Alín subverting the trope rather than fulfilling it.

AGONIZING BUILDUP, INSTANTANEOUS IMPLOSION

The plot of the Inheritance Cycle was simplistic and extremely derivative, yet Paolini made something entertaining out of it. He took elements that could have been weaknesses and leveraged them into strengths. Out of something weak and predictable came a genuinely entertaining experience.

The plot of Murtagh is a derivative of the Inheritance Cycle, spat out by someone whose writing process consists of saying, “Well, this successful book series did it,” without any ounce of understanding as to why the story being copied actually worked. It is boring, insulting, and ultimately a waste of time.

What’s more, Paolini makes decisions here that actively undermine the Inheritance Cycle and damage future stories. These were not necessary decisions. At best, they were shortcuts. By making these choices, Paolini sacrificed a great series to prop up an inadequate sequel. It does not fill me with confidence for a book V and beyond.

On November 22nd, we will roll up our sleeves and dredge up exactly how and why it all went so wrong. I hope to see you all then. Have a good week.